tup = (4, 5, 6)

tup(4, 5, 6)

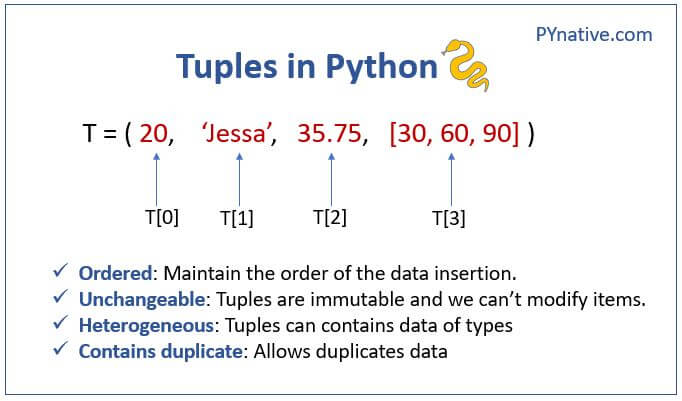

A tuple is a fixed-length, immutable sequence of Python objects which, once assigned, cannot be changed. The easiest way to create one is with a comma-separated sequence of values wrapped in parentheses:

tup = (4, 5, 6)

tup(4, 5, 6)In many contexts, the parentheses can be omitted

tup = 4, 5, 6

tup(4, 5, 6)You can convert any sequence or iterator to a tuple by invoking

tuple([4,0,2])

tup = tuple('string')

tup('s', 't', 'r', 'i', 'n', 'g')Elements can be accessed with square brackets []

Note the zero indexing

tup[0]'s'Tuples of tuples

nested_tup = (4,5,6),(7,8)

nested_tup((4, 5, 6), (7, 8))nested_tup[0](4, 5, 6)nested_tup[1](7, 8)While the objects stored in a tuple may be mutable themselves, once the tuple is created it’s not possible to modify which object is stored in each slot:

tup = tuple(['foo', [1, 2], True])

tup[2]True```{python}

tup[2] = False

```TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [9], in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1 tup[2] = False

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentIf an object inside a tuple is mutable, such as a list, you can modify it in place

tup[1].append(3)

tup('foo', [1, 2, 3], True)You can concatenate tuples using the + operator to produce longer tuples:

(4, None, 'foo') + (6, 0) + ('bar',)(4, None, 'foo', 6, 0, 'bar')If you try to assign to a tuple-like expression of variables, Python will attempt to unpack the value on the righthand side of the equals sign:

tup = (4, 5, 6)

tup(4, 5, 6)a, b, c = tup

c6Even sequences with nested tuples can be unpacked:

tup = 4, 5, (6,7)

a, b, (c, d) = tup

d7To easily swap variable names

a, b = 1, 4

a1b4b, a = a, b

a4b1A common use of variable unpacking is iterating over sequences of tuples or lists

seq = [(1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)]

seq[(1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)]for a, b, c in seq:

print(f'a={a}, b={b}, c={c}')a=1, b=2, c=3

a=4, b=5, c=6

a=7, b=8, c=9*rest syntax for plucking elements

values = 1,2,3,4,5

a, b, *rest = values

rest[3, 4, 5]As a matter of convention, many Python programmers will use the underscore (_) for unwanted variables:

a, b, *_ = valuesSince the size and contents of a tuple cannot be modified, it is very light on instance methods. A particularly useful one (also available on lists) is count

a = (1,2,2,2,2,3,4,5,7,8,9)

a.count(2)4

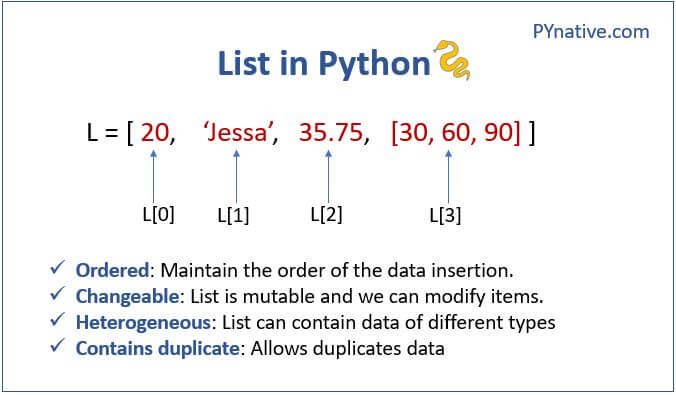

In contrast with tuples, lists are variable length and their contents can be modified in place.

Lists are mutable.

Lists use [] square brackts or the list function

a_list = [2, 3, 7, None]

tup = ("foo", "bar", "baz")

b_list = list(tup)

b_list['foo', 'bar', 'baz']b_list[1] = "peekaboo"

b_list['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz']Lists and tuples are semantically similar (though tuples cannot be modified) and can be used interchangeably in many functions.

gen = range(10)

genrange(0, 10)list(gen)[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]the append method

b_list.append("dwarf")

b_list['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']the insert method

b_list.insert(1, "red")

b_list['foo', 'red', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']insert is computationally more expensive than append

the pop method, the inverse of insert

b_list.pop(2)'peekaboo'b_list['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'dwarf']the remove method

b_list.append("foo")

b_list['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'dwarf', 'foo']b_list.remove("foo")

b_list['red', 'baz', 'dwarf', 'foo']Check if a list contains a value using the in keyword:

"dwarf" in b_listTrueThe keyword not can be used to negate an in

"dwarf" not in b_listFalsesimilar with tuples, use + to concatenate

[4, None, "foo"] + [7, 8, (2, 3)][4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]the extend method

x = [4, None, "foo"]

x.extend([7,8,(2,3)])

x[4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]list concatenation by addition is an expensive operation

using extend is preferable

```{python}

everything = []

for chunk in list_of_lists:

everything.extend(chunk)

```is generally faster than

```{python}

everything = []

for chunk in list_of_lists:

everything = everything + chunk

```the sort method

a = [7, 2, 5, 1, 3]

a.sort()

a[1, 2, 3, 5, 7]sort options

b = ["saw", "small", "He", "foxes", "six"]

b.sort(key = len)

b['He', 'saw', 'six', 'small', 'foxes']Slicing semantics takes a bit of getting used to, especially if you’re coming from R or MATLAB.

using the indexing operator []

seq = [7, 2, 3, 7, 5, 6, 0, 1]

seq[3:5][7, 5]also assigned with a sequence

seq[3:5] = [6,3]

seq[7, 2, 3, 6, 3, 6, 0, 1]Either the start or stop can be omitted

seq[:5][7, 2, 3, 6, 3]seq[3:][6, 3, 6, 0, 1]Negative indices slice the sequence relative to the end:

seq[-4:][3, 6, 0, 1]A step can also be used after a second colon to, say, take every other element:

seq[::2][7, 3, 3, 0]A clever use of this is to pass -1, which has the useful effect of reversing a list or tuple:

seq[::-1][1, 0, 6, 3, 6, 3, 2, 7]

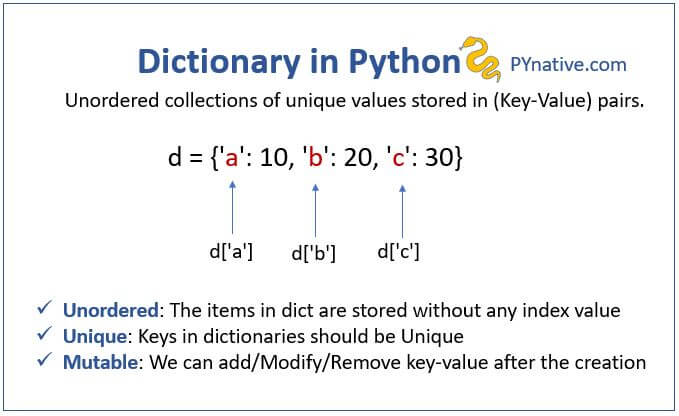

The dictionary or dict may be the most important built-in Python data structure.

One approach for creating a dictionary is to use curly braces {} and colons to separate keys and values:

empty_dict = {}

d1 = {"a": "some value", "b": [1, 2, 3, 4]}

d1{'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4]}access, insert, or set elements

d1[7] = "an integer"

d1{'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4], 7: 'an integer'}and as before

"b" in d1Truethe del and pop methods

del d1[7]

d1{'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4]}ret = d1.pop("a")

ret'some value'The keys and values methods

list(d1.keys())['b']list(d1.values())[[1, 2, 3, 4]]the items method

list(d1.items())[('b', [1, 2, 3, 4])]the update method to merge one dictionary into another

d1.update({"b": "foo", "c": 12})

d1{'b': 'foo', 'c': 12}### Creating dictionaries from sequences

list(range(5))[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]tuples = zip(range(5), reversed(range(5)))

tuples

mapping = dict(tuples)

mapping{0: 4, 1: 3, 2: 2, 3: 1, 4: 0}imagine categorizing a list of words by their first letters as a dictionary of lists

words = ["apple", "bat", "bar", "atom", "book"]

by_letter = {}

for word in words:

letter = word[0]

if letter not in by_letter:

by_letter[letter] = [word]

else:

by_letter[letter].append(word)

by_letter{'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']}The setdefault dictionary method can be used to simplify this workflow. The preceding for loop can be rewritten as:

by_letter = {}

for word in words:

letter = word[0]

by_letter.setdefault(letter, []).append(word)

by_letter{'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']}The built-in collectionsmodule has a useful class, defaultdict, which makes this even easier.

from collections import defaultdict

by_letter = defaultdict(list)

for word in words:

by_letter[word[0]].append(word)

by_letterdefaultdict(list, {'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']})keys generally have to be immutable objects like scalars or tuples for hashability

To use a list as a key, one option is to convert it to a tuple, which can be hashed as long as its elements also can be:

d = {}

d[tuple([1,2,3])] = 5

d{(1, 2, 3): 5}

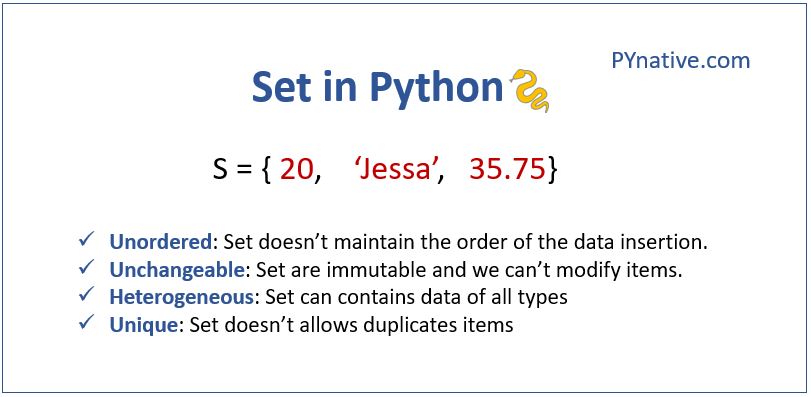

can be created in two ways: via the set function or via a set literal with curly braces:

set([2, 2, 2, 1, 3, 3])

{2,2,1,3,3}{1, 2, 3}Sets support mathematical set operations like union, intersection, difference, and symmetric difference.

The union of these two sets:

a = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b = {3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

a.union(b)

a | b{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}The &operator or the intersection method

a.intersection(b)

a & b{3, 4, 5}A table of commonly used set methods

All of the logical set operations have in-place counterparts, which enable you to replace the contents of the set on the left side of the operation with the result. For very large sets, this may be more efficient

c = a.copy()

c |= b

c{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}d = a.copy()

d &= b

d{3, 4, 5}set elements generally must be immutable, and they must be hashable

you can convert them to tuples

You can also check if a set is a subset of (is contained in) or a superset of (contains all elements of) another set

a_set = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

{1, 2, 3}.issubset(a_set)Truea_set.issuperset({1, 2, 3})Trueenumerate returns a sequence of (i, value) tuples

sorted returns a new sorted list

sorted([7,1,2,9,3,6,5,0,22])[0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 22]zip “pairs” up the elements of a number of lists, tuples, or other sequences to create a list of tuples

seq1 = ["foo", "bar", "baz"]

seq2 = ["one", "two", "three"]

zipped = zip(seq1, seq2)

list(zipped)[('foo', 'one'), ('bar', 'two'), ('baz', 'three')]zip can take an arbitrary number of sequences, and the number of elements it produces is determined by the shortest sequence

seq3 = [False, True]

list(zip(seq1, seq2, seq3))[('foo', 'one', False), ('bar', 'two', True)]A common use of zip is simultaneously iterating over multiple sequences, possibly also combined with enumerate

for index, (a, b) in enumerate(zip(seq1, seq2)):

print(f"{index}: {a}, {b}")0: foo, one

1: bar, two

2: baz, threereversed iterates over the elements of a sequence in reverse order

list(reversed(range(10)))[9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0][expr for value in collection if condition]For example, given a list of strings, we could filter out strings with length 2 or less and convert them to uppercase like this

strings = ["a", "as", "bat", "car", "dove", "python"]

[x.upper() for x in strings if len(x) > 2]['BAT', 'CAR', 'DOVE', 'PYTHON']A dictionary comprehension looks like this

dict_comp = {key-expr: value-expr for value in collection

if condition}Suppose we wanted a set containing just the lengths of the strings contained in the collection

unique_lengths = {len(x) for x in strings}

unique_lengths{1, 2, 3, 4, 6}we could create a lookup map of these strings for their locations in the list

loc_mapping = {value: index for index, value in enumerate(strings)}

loc_mapping{'a': 0, 'as': 1, 'bat': 2, 'car': 3, 'dove': 4, 'python': 5}Suppose we have a list of lists containing some English and Spanish names. We want to get a single list containing all names with two or more a’s in them

all_data = [["John", "Emily", "Michael", "Mary", "Steven"],

["Maria", "Juan", "Javier", "Natalia", "Pilar"]]

result = [name for names in all_data for name in names

if name.count("a") >= 2]

result['Maria', 'Natalia']Here is another example where we “flatten” a list of tuples of integers into a simple list of integers

some_tuples = [(1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)]

flattened = [x for tup in some_tuples for x in tup]

flattened[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Functions are the primary and most important method of code organization and reuse in Python.

they use the def keyword

Each function can have positional arguments and keyword arguments. Keyword arguments are most commonly used to specify default values or optional arguments. Here we will define a function with an optional z argument with the default value 1.5

def my_function(x, y, z=1.5):

return (x + y) * z

my_function(4,25)43.5The main restriction on function arguments is that the keyword arguments must follow the positional arguments

A more descriptive name describing a variable scope in Python is a namespace.

Consider the following function

a = []

def func():

for i in range(5):

a.append(i)When func() is called, the empty list a is created, five elements are appended, and then a is destroyed when the function exits.

func()

func()

a[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4]What’s happening here is that the function is actually just returning one object, a tuple, which is then being unpacked into the result variables.

def f():

a = 5

b = 6

c = 7

return a, b, c

a, b, c = f()

a5Suppose we were doing some data cleaning and needed to apply a bunch of transformations to the following list of strings:

states = [" Alabama ", "Georgia!", "Georgia", "georgia", "FlOrIda",

"south carolina##", "West virginia?"]

import re

def clean_strings(strings):

result = []

for value in strings:

value = value.strip()

value = re.sub("[!#?]", "", value)

value = value.title()

result.append(value)

return result

clean_strings(states)['Alabama',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']Another approach

def remove_punctuation(value):

return re.sub("[!#?]", "", value)

clean_ops = [str.strip, remove_punctuation, str.title]

def clean_strings(strings, ops):

result = []

for value in strings:

for func in ops:

value = func(value)

result.append(value)

return result

clean_strings(states, clean_ops)['Alabama',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']You can use functions as arguments to other functions like the built-in map function

for x in map(remove_punctuation, states):

print(x) Alabama

Georgia

Georgia

georgia

FlOrIda

south carolina

West virginiaa way of writing functions consisting of a single statement

suppose you wanted to sort a collection of strings by the number of distinct letters in each string

strings = ["foo", "card", "bar", "aaaaaaa", "ababdo"]

strings.sort(key=lambda x: len(set(x)))

strings['aaaaaaa', 'foo', 'bar', 'card', 'ababdo']Many objects in Python support iteration, such as over objects in a list or lines in a file.

some_dict = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3}

for key in some_dict:

print(key)a

b

cMost methods expecting a list or list-like object will also accept any iterable object. This includes built-in methods such as min, max, and sum, and type constructors like list and tuple

A generator is a convenient way, similar to writing a normal function, to construct a new iterable object. Whereas normal functions execute and return a single result at a time, generators can return a sequence of multiple values by pausing and resuming execution each time the generator is used. To create a generator, use the yield keyword instead of return in a function

def squares(n=10):

print(f"Generating squares from 1 to {n ** 2}")

for i in range(1, n + 1):

yield i ** 2

gen = squares()

for x in gen:

print(x, end=" ")Generating squares from 1 to 100

1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100 Since generators produce output one element at a time versus an entire list all at once, it can help your program use less memory.

This is a generator analogue to list, dictionary, and set comprehensions. To create one, enclose what would otherwise be a list comprehension within parentheses instead of brackets:

gen = (x ** 2 for x in range(100))

gen<generator object <genexpr> at 0x000001A3294B9C10>Generator expressions can be used instead of list comprehensions as function arguments in some cases:

sum(x ** 2 for x in range(100))328350dict((i, i ** 2) for i in range(5)){0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16}itertools module has a collection of generators for many common data algorithms.

groupby takes any sequence and a function, grouping consecutive elements in the sequence by return value of the function

import itertools

def first_letter(x):

return x[0]

names = ["Alan", "Adam", "Jackie", "Lily", "Katie", "Molly"]

for letter, names in itertools.groupby(names, first_letter):

print(letter, list(names))A ['Alan', 'Adam']

J ['Jackie']

L ['Lily']

K ['Katie']

M ['Molly']Handling errors or exceptions gracefully is an important part of building robust programs

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except:

return x

attempt_float("1.2345")1.2345attempt_float("something")'something'You might want to suppress only ValueError, since a TypeError (the input was not a string or numeric value) might indicate a legitimate bug in your program. To do that, write the exception type after except:

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except ValueError:

return xattempt_float((1, 2))---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

d:\packages\bookclub-py4da\03_notes.qmd in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1001 attempt_float((1, 2))

Input In [114], in attempt_float(x)

1 def attempt_float(x):

2 try:

----> 3 return float(x)

4 except ValueError:

5 return x

TypeError: float() argument must be a string or a real number, not 'tuple'

You can catch multiple exception types by writing a tuple of exception types instead (the parentheses are required):

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except (TypeError, ValueError):

return x

attempt_float((1, 2))(1, 2)In some cases, you may not want to suppress an exception, but you want some code to be executed regardless of whether or not the code in the try block succeeds. To do this, use finally:

f = open(path, mode="w")

try:

write_to_file(f)

finally:

f.close()Here, the file object f will always get closed.

you can have code that executes only if the try: block succeeds using else:

f = open(path, mode="w")

try:

write_to_file(f)

except:

print("Failed")

else:

print("Succeeded")

finally:

f.close()If an exception is raised while you are %run-ing a script or executing any statement, IPython will by default print a full call stack trace. Having additional context by itself is a big advantage over the standard Python interpreter

To open a file for reading or writing, use the built-in open function with either a relative or absolute file path and an optional file encoding.

We can then treat the file object f like a list and iterate over the lines

path = "examples/segismundo.txt"

f = open(path, encoding="utf-8")

lines = [x.rstrip() for x in open(path, encoding="utf-8")]

linesWhen you use open to create file objects, it is recommended to close the file

f.close()some of the most commonly used methods are read, seek, and tell.

read(10) returns 10 characters from the file

the read method advances the file object position by the number of bytes read

tell() gives you the current position in the file

To get consistent behavior across platforms, it is best to pass an encoding (such as encoding="utf-8")

seek(3) changes the file position to the indicated byte

To write text to a file, you can use the file’s write or writelines methods

The default behavior for Python files (whether readable or writable) is text mode, which means that you intend to work with Python strings (i.e., Unicode).