Expressions

Learning objectives:

- Understand the idea of the abstract syntax tree (AST).

- Discuss the data structures that underlie the AST:

- Constants

- Symbols

- Calls

- Explore the idea behind parsing.

- Explore some details of R’s grammar.

- Discuss the use or recursive functions to compute on the language.

- Work with three other more specialized data structures:

- Pairlists

- Missing arguments

- Expression vectors

Introduction

To compute on the language, we first need to understand its structure.

- This requires a few things:

- New vocabulary.

- New tools to inspect and modify expressions.

- Approach the use of the language with new ways of thinking.

- One of the first new ways of thinking is the distinction between an operation and its result.

- We can capture the intent of the code without executing it using the rlang package.

- We can then evaluate the expression using the base::eval function.

Evaluating multiple expressions

The function

expression()allows for multiple expressions, and in some ways it acts similarly to the way files aresource()d in. That is, weeval()uate all of the expressions at once.expression()returns a vector and can be passed toeval().

#> [1] 40#> [1] FALSE#> [1] TRUEexprs()does not evaluate everything at once. To evaluate each expression, the individual expressions must be evaluated in a loop.

Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)

- Expressions are objects that capture the structure of code without evaluating it.

- Expressions are also called abstract syntax trees (ASTs) because the structure of code is hierarchical and can be naturally represented as a tree.

- Understanding this tree structure is crucial for inspecting and modifying expressions.

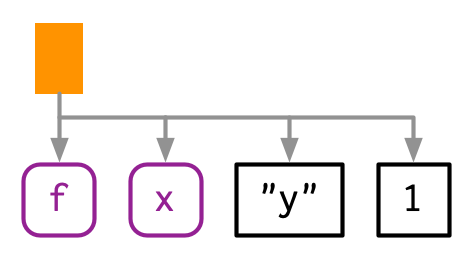

- Branches = Calls

- Leaves = Symbols and constants

With lobstr::ast():

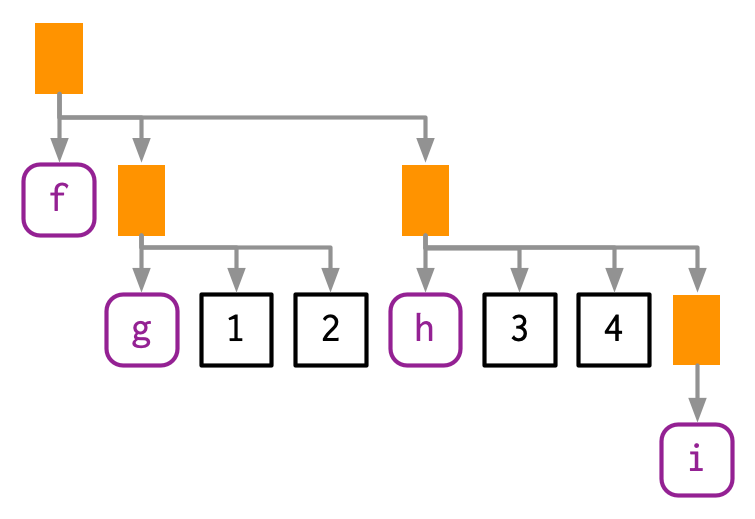

- Some functions might also contain more calls like the example below:

#> █─f

#> ├─█─g

#> │ ├─1

#> │ └─2

#> └─█─h

#> ├─3

#> ├─4

#> └─█─i- Read the hand-drawn diagrams from left-to-right (ignoring vertical position)

- Read the lobstr-drawn diagrams from top-to-bottom (ignoring horizontal position).

- The depth within the tree is determined by the nesting of function calls.

- Depth also determines evaluation order, as evaluation generally proceeds from deepest-to-shallowest, but this is not guaranteed because of lazy evaluation.

Infix calls

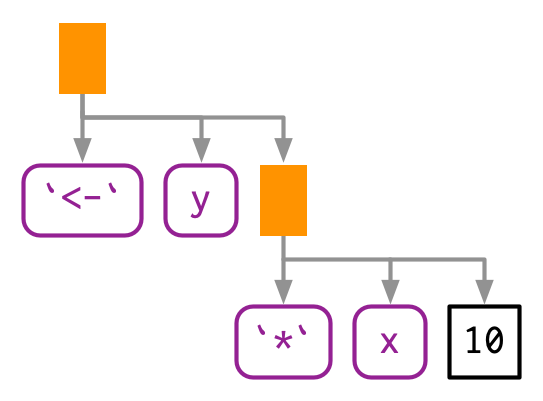

Every call in R can be written in tree form because any call can be written in prefix form.

An infix operator is a function where the function name is placed between its arguments. Prefix form is when then function name comes before the arguments, which are enclosed in parentheses. [Note that the name infix comes from the words prefix and suffix.]

- A characteristic of the language is that infix functions can always be written as prefix functions; therefore, all function calls can be represented using an AST.

- There is no difference between the ASTs for the infix version vs the prefix version, and if you generate an expression with prefix calls, R will still print it in infix form:

Expression

- Collectively, the data structures present in the AST are called expressions.

- These include:

- Constants

- Symbols

- Calls

- Pairlists

Constants

- Scalar constants are the simplest component of the AST.

- A constant is either NULL or a length-1 atomic vector (or scalar)

- e.g.,

TRUE,1L,2.5,"x", or"hello".

- e.g.,

- We can test for a constant with

rlang::is_syntactic_literal(). - Constants are self-quoting in the sense that the expression used to represent a constant is the same constant:

#> [1] TRUE#> [1] TRUE#> [1] TRUE#> [1] TRUE#> [1] TRUESymbols

- A symbol represents the name of an object.

xmtcarsmean

- In base R, the terms symbol and name are used interchangeably (i.e.,

is.name()is identical tois.symbol()), but this book used symbol consistently because “name” has many other meanings. - You can create a symbol in two ways:

- by capturing code that references an object with

expr(). - turning a string into a symbol with

rlang::sym().

- by capturing code that references an object with

- A symbol can be turned back into a string with

as.character()orrlang::as_string(). as_string()has the advantage of clearly signalling that you’ll get a character vector of length 1.

- We can recognize a symbol because it is printed without quotes

str()tells you that it is a symbol, andis.symbol()is TRUE:

- The symbol type is not vectorised, i.e., a symbol is always length 1.

- If you want multiple symbols, you’ll need to put them in a list, using

rlang::syms().

Note that as_string() will not work on expressions which are not symbols.

Calls

- A call object represents a captured function call.

- Call objects are a special type of list.

- The first component specifies the function to call (usually a symbol, i.e., the name fo the function).

- The remaining elements are the arguments for that call.

- Call objects create branches in the AST, because calls can be nested inside other calls.

- You can identify a call object when printed because it looks just like a function call.

- Confusingly

typeof()andstr()print language for call objects (where we might expect it to return that it is a “call” object), butis.call()returns TRUE:

#> █─read.table

#> ├─"important.csv"

#> └─row.names = FALSESubsetting

- Calls generally behave like lists.

- Since they are list-like, you can use standard subsetting tools.

- The first element of the call object is the function to call, which is usually a symbol:

- The remainder of the elements are the arguments:

#> [1] FALSE#> [[1]]

#> [1] "important.csv"

#>

#> $row.names

#> [1] FALSE- We can extract individual arguments with [[ or, if named, $:

- We can determine the number of arguments in a call object by subtracting 1 from its length:

- Extracting specific arguments from calls is challenging because of R’s flexible rules for argument matching:

- It could potentially be in any location, with the full name, with an abbreviated name, or with no name.

- To work around this problem, you can use

rlang::call_standardise()which standardizes all arguments to use the full name:

#> Warning: `call_standardise()` is deprecated as of rlang 0.4.11

#> This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.#> read.table(file = "important.csv", row.names = FALSE)- But If the function uses … it’s not possible to standardise all arguments.

- Calls can be modified in the same way as lists:

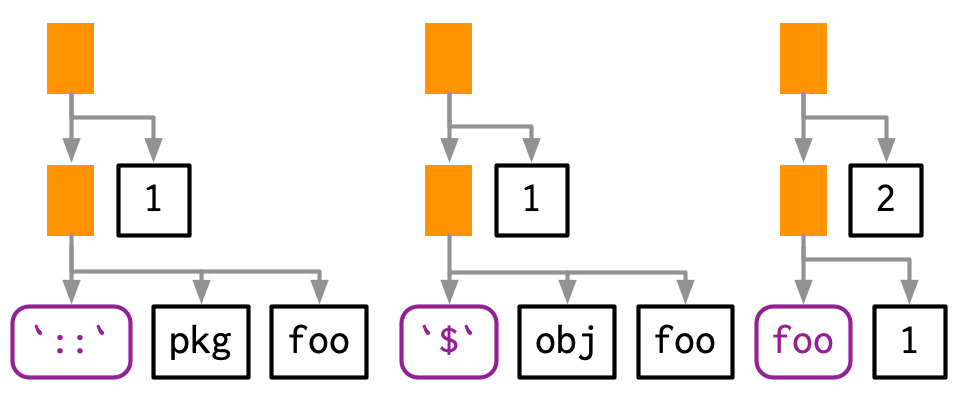

Function position

- The first element of the call object is the function position. This contains the function that will be called when the object is evaluated, and is usually a symbol.

- While R allows you to surround the name of the function with quotes, the parser converts it to a symbol:

- However, sometimes the function doesn’t exist in the current environment and you need to do some computation to retrieve it:

- For example, if the function is in another package, is a method of an R6 object, or is created by a function factory. In this case, the function position will be occupied by another call:

Constructing

- You can construct a call object from its components using

rlang::call2(). - The first argument is the name of the function to call (either as a string, a symbol, or another call).

- The remaining arguments will be passed along to the call:

- Infix calls created in this way still print as usual.

Parsing and grammar

- Parsing - The process by which a computer language takes a string and constructs an expression. Parsing is governed by a set of rules known as a grammar.

- We are going to use

lobstr::ast()to explore some of the details of R’s grammar, and then show how you can transform back and forth between expressions and strings. - Operator precedence - Conventions used by the programming language to resolve ambiguity.

- Infix functions introduce two sources of ambiguity.

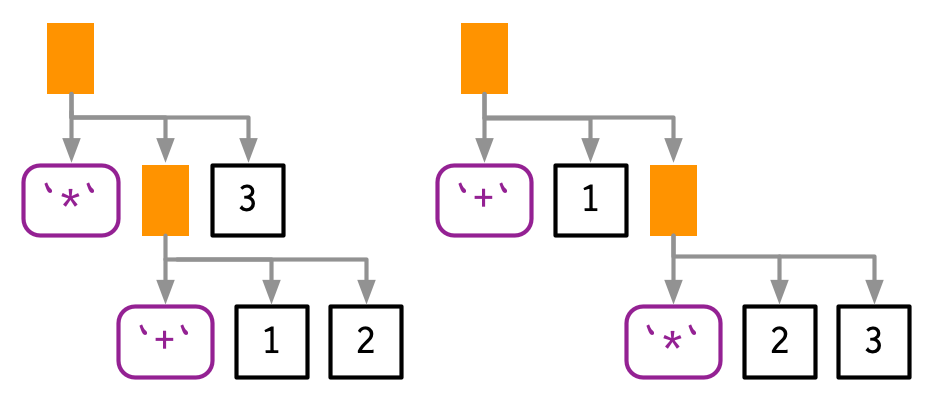

- The first source of ambiguity arises from infix functions: what does 1 + 2 * 3 yield? Do you get 9 (i.e., (1 + 2) * 3), or 7 (i.e., 1 + (2 * 3))? In other words, which of the two possible parse trees below does R use?

- Programming languages use conventions called operator precedence to resolve this ambiguity. We can use

ast()to see what R does:

- PEMDAS (or BEDMAS or BODMAS, depending on where in the world you grew up) is pretty clear on what to do. Other operator precedence isn’t as clear.

- There’s one particularly surprising case in R:

- ! has a much lower precedence (i.e., it binds less tightly) than you might expect.

- This allows you to write useful operations like:

- R has over 30 infix operators divided into 18 precedence groups.

- While the details are described in

?Syntax, very few people have memorized the complete ordering. - If there’s any confusion, use parentheses!

#> █─`*`

#> ├─█─`(`

#> │ └─█─`+`

#> │ ├─1

#> │ └─2

#> └─3Associativity

- The second source of ambiguity is introduced by repeated usage of the same infix function.

In this case it doesn’t matter. Other places it might, like in

ggplot2.In R, most operators are left-associative, i.e., the operations on the left are evaluated first:

- There are two exceptions to the left-associative rule:

- exponentiation

- assignment

Parsing and deparsing

- Parsing - turning characters you’ve typed into an AST (i.e., from strings to expressions).

- R usually takes care of parsing code for us.

- But occasionally you have code stored as a string, and you want to parse it yourself.

- You can do so using

rlang::parse_expr():

parse_expr()always returns a single expression.- If you have multiple expression separated by

;or,, you’ll need to userlang::parse_exprs()which is the plural version ofrlang::parse_expr(). It returns a list of expressions:

- If you find yourself parsing strings into expressions often, quasiquotation may be a safer approach.

- More about quasiquaotation in Chapter 19.

- The inverse of parsing is deparsing.

- Deparsing - given an expression, you want the string that would generate it.

- Deparsing happens automatically when you print an expression.

- You can get the string with

rlang::expr_text(): - Parsing and deparsing are not symmetric.

- Parsing creates the AST which means that we lose backticks around ordinary names, comments, and whitespace.

Using the AST to solve more complicated problems

- Here we focus on what we learned to perform recursion on the AST.

- Two parts of a recursive function:

- Recursive case: handles the nodes in the tree. Typically, you’ll do something to each child of a node, usually calling the recursive function again, and then combine the results back together again. For expressions, you’ll need to handle calls and pairlists (function arguments).

- Base case: handles the leaves of the tree. The base cases ensure that the function eventually terminates, by solving the simplest cases directly. For expressions, you need to handle symbols and constants in the base case.

Two helper functions

- First, we need an

epxr_type()function to return the type of expression element as a string.

#> [1] "constant"#> [1] "symbol"#> [1] "call"- Second, we need a wrapper function to handle exceptions.

- Lastly, we can write a basic template that walks the AST using the

switch()statement.

Specific use cases for recurse_call()

Example 1: Finding F and T

- Using

FandTin our code rather thanFALSEandTRUEis bad practice. - Say we want to walk the AST to find times when we use

FandT. - Start off by finding the type of

TvsTRUE.

- With this knowledge, we can now write the base cases of our recursive function.

- The logic is as follows:

- A constant is never a logical abbreviation and a symbol is an abbreviation if it is “F” or “T”:

- It’s best practice to write another wrapper, assuming every input you receive will be an expression.

#> [1] TRUE#> [1] FALSENext step: code for the recursive cases

- Here we want to do the same thing for calls and for pairlists.

- Here’s the logic: recursively apply the function to each subcomponent, and return

TRUEif any subcomponent contains a logical abbreviation. - This is simplified by using the

purrr::some()function, which iterates over a list and returnsTRUEif the predicate function is true for any element.

logical_abbr_rec <- function(x) {

switch_expr(x,

# Base cases

constant = FALSE,

symbol = as_string(x) %in% c("F", "T"),

# Recursive cases

call = ,

# Are we sure this is the correct function to use?

# Why not logical_abbr_rec?

pairlist = purrr::some(x, logical_abbr_rec)

)

}

logical_abbr(mean(x, na.rm = T))#> [1] TRUE#> [1] TRUEExample 2: Finding all variables created by assignment

- Listing all the variables is a little more complicated.

- Figure out what assignment looks like based on the AST.

- Now we need to decide what data structure we’re going to use for the results.

- Easiest thing will be to return a character vector.

- We would need to use a list if we wanted to return symbols.

Dealing with the base cases

#> character(0)#> character(0)Dealing with the recursive cases

- Here is the function to flatten pairlists.

#> [1] "a" "a" "b" "b" "c" "c"- Here is the code needed to identify calls.

#> [1] "a"#> [1] "a" "b"Make the function more robust

- Throw cases at it that we think might break the function.

- Write a function to handle these cases.

find_assign_call <- function(x) {

if (is_call(x, "<-") && is_symbol(x[[2]])) {

lhs <- as_string(x[[2]])

children <- as.list(x)[-1]

} else {

lhs <- character()

children <- as.list(x)

}

c(lhs, flat_map_chr(children, find_assign_rec))

}

find_assign_rec <- function(x) {

switch_expr(x,

# Base cases

constant = ,

symbol = character(),

# Recursive cases

pairlist = flat_map_chr(x, find_assign_rec),

call = find_assign_call(x)

)

}

find_assign(a <- b <- c <- 1)#> [1] "a" "b" "c"#> [1] "x" "y"- This approach certainly is more complicated, but it’s important to start simple and move up.

Specialised data structures

- Pairlists

- Missing arguments

- Expression vectors

Pairlists

- Pairlists are a remnant of R’s past and have been replaced by lists almost everywhere.

- The only place you are likely to see pairlists in R is when working with calls to the function, as the formal arguments to a function are stored in a pairlist:

- Fortunately, whenever you encounter a pairlist, you can treat it just like a regular list:

Missing arguments

- Empty symbols

- To create an empty symbol, you need to use

missing_arg()orexpr().

- Empty symbols don’t print anything.

- To check, we need to use

rlang::is_missing()

- To check, we need to use

- These are usually present in function formals:

Expression vectors

- An expression vector is just a list of expressions.

- The only difference is that calling

eval()on an expression evaluates each individual expression. - Instead, it might be more advantageous to use a list of expressions.

- The only difference is that calling

- Expression vectors are only produced by two base functions:

expression()andparse():

- Like calls and pairlists, expression vectors behave like lists: