S4

Learning objectives

- Identify the main components of S4 objects, including the new slot component

- Learn best practices for creating new S4 classes and creating/modifying/accessing their objects

- “Understand” multiple inheritance, multiple dispatch, and appreciate their risks and complexity

Not learning objectives

- How to most effectively deploy S4

- No single reference.

- Existing references often conflict.

Basics

All functions related to S4 live in the {methods} package

Tip

Best practice to explicitly call library(methods) since it is not loaded by default in non-interactive environments (i.e. Rscript)

setClass() defines an S4 class and its slots; new() creates a new object

Access slots with @ or slot(), but don’t use it outside of your own methods

Supply accessor functions for others to use with your class

Tip

Look for accessor functions when working with classes maintained by others

{sloop} can help you identify S4 objects and generics

Classes

setClass() has 4 arguments you should use. The rest should be ignored.

Classsets the class name.- By convention use

UpperCamelCase

- By convention use

slotssets the available slots (fields) using a named character vector of classesprototypelist default values for each slot- Always provide

prototype, even though its optional

- Always provide

containsspecifies classes to inherit slots from

setClass() has 4 arguments you should use. The rest should be ignored.

setClass() has 4 arguments you should use. The rest should be ignored.

#> Formal class 'Employee' [package ".GlobalEnv"] with 3 slots

#> ..@ boss:Formal class 'Person' [package ".GlobalEnv"] with 2 slots

#> .. .. ..@ name: chr NA

#> .. .. ..@ age : num NA

#> ..@ name: chr NA

#> ..@ age : num NAsetClass() has 4 arguments you should use. The rest should be ignored.

Caution

Use setClass() with care. It’s possible to create invalid objects if you redefine a class after already having instantiated an object.

Use is() to determine an objects classes or test for a specific class

User-facing classes should be paired with a helper function to create new objects

- Use the same name as the class.

- Craft user interface with carefully chosen defaults and useful conversions.

- Craft error messages tailored towards an end-user.

- Finish by calling

methods::new().

Create a validator to enforce rules around slot values

- S4 automatically checks slots for the correct class

- Use

setValidity()to enforce more complex rules - Check validity with

validObject()

Caution

Validity is only called automatically by new(). Slots can be modified with invalid values.

Generics & Methods

Create an S4 generic with setGeneric() and standardGeneric()

- By convention use

lowerCamelCase

Use the signature argument of setGeneric() to help control dispatch

- Without

signatureall arguments (except for...) are considered during dispatch - Helpful for adding arguments like

verbose = TRUEandquiet = FALSE

Define methods using setMethod()

- Only use the following 3 arguments (never use others)

f: the name of the genericsignature: class or classes to use for dispatchdefinition: the function definition for the method

The show() method controls how the object is printed.

- It is the most commonly defined S4 method

All user-accessible slots should be accompanied by a pair of accessors

One for reading…

All user-accessible slots should be accompanied by a pair of accessors

…and one for writing.

#> [1] "name<-"#> [1] "Jon Smythe"Tip

Always include validObject() in the setter function.

Use methods() and selectMethods() to investigate available methods for a generic or class

#> [1] age,Person-method

#> see '?methods' for accessing help and source code#> [1] age age<- name name<- show

#> see '?methods' for accessing help and source code#> Method Definition:

#>

#> function (x)

#> x@age

#>

#> Signatures:

#> x

#> target "Person"

#> defined "Person"Method Dispatch

S4 dispatch is complicated!

- Multiple inheritance, i.e. a class can have multiple parents

- Multiple dispatch, i.e. a generic can use multiple arguments to pick a method.

Tip

Keep method dispatch as simple as possible by avoiding multiple inheritance, and reserving multiple dispatch only for where it is absolutely necessary.

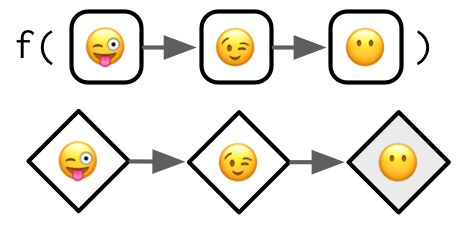

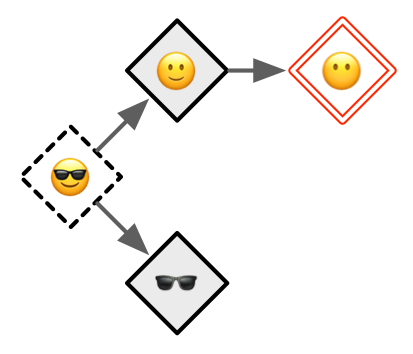

It can help to visualize dispatch as a graph

Single dispatch is straight forward

Pseudo-classes ANY and MISSING can help define useful behaviors

ANYmatches any class and is always at the end of a method graph

MISSINGmatches whenever an argument is missing- Useful for functions like

+and-

- Useful for functions like

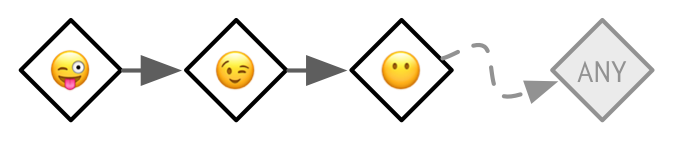

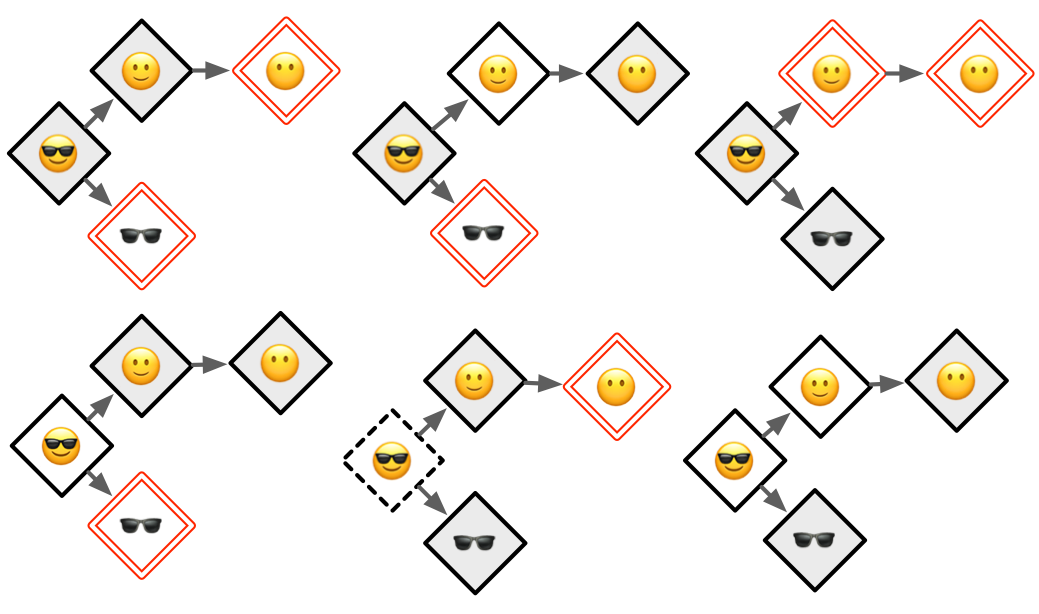

Multiple inheritance is tricky

Class with the shortest distance to the specified class gets dispatched.

Multiple inheritance can lead to ambiguous method dispatch

- Methods of equal distance cause ambiguous method dispatch and generate a warning

- Always resolve ambiguity by providing a more precise method

Use multiple inheritance with extreme care

It is hard to prevent ambiguity, ensure every terminal method has an implementation, and minimize the number of defined methods.

Only one of the above calls is free from problems.

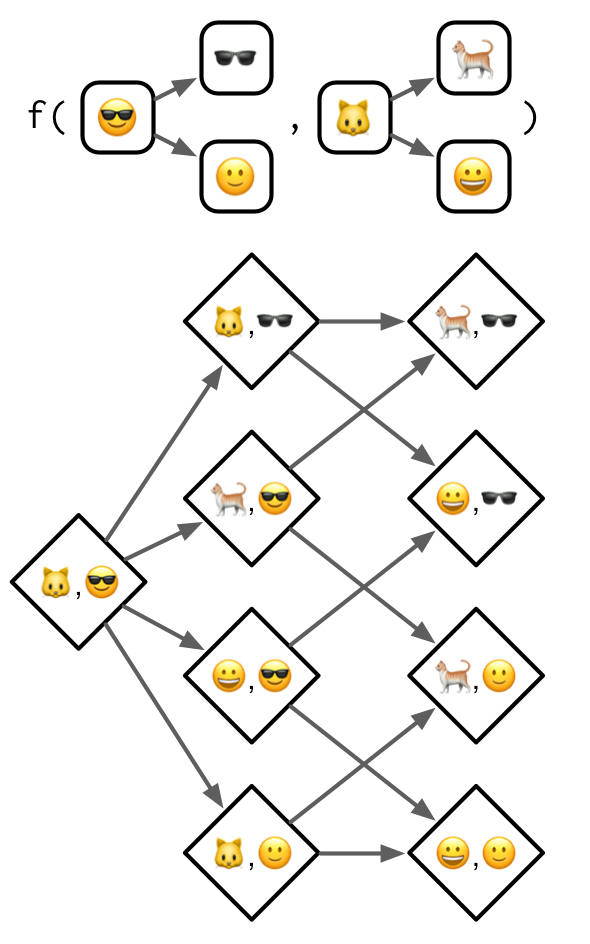

Multiple dispatch is less tricky to work with than multiple inheritance

- Fewer terminal class combinations allow you to define a single method and have default behavior

Classes are separated by a comma

Multiple dispatch with multiple inheritance is complex 😵💫

Two classes each with multiple inheritance

Mixing S4 & S3

S3 must first be registered with setOldClass() before inclusion in S4

Can be as simple as

S3 must first be registered with setOldClass() before inclusion in S4

But better to specify a full S4 definition

Caution

These definitions should be provided by the creator of the S3 class. Don’t trying building an S4 class on top of an S3 class provided by a package. Instead request that the package maintainer add this call to their package.

S4 classes receive as special .Data slot when inheriting from S3 or base types

S3 generics are easily converted to S4 generics

#> Method Definition (Class "derivedDefaultMethod"):

#>

#> function (x, ...)

#> UseMethod("mean")

#> <bytecode: 0x00000157b589e8c8>

#> <environment: namespace:base>

#>

#> Signatures:

#> x

#> target "ANY"

#> defined "ANY"Caution

It is OK to convert an existing S3 generic to S4, but you should avoid converting regular functions to S4 generics

Exercises

lubridate::period() returns an S4 class. What slots does it have? What class is each slot? What accessors does it provide?

Objects of the S4 Period class have six slots named year, month, day, hour, minute, and .Data (which contains the number of seconds). All slots are of type double. Most fields can be retrieved by an identically named accessor (e.g. lubridate::year() will return the field), use second() to get the .Data slot.

As a short example, we create a period of 1 second, 2 minutes, 3 hours, 4 days and 5 weeks.

This should add up to a period of 39 days, 3 hours, 2 minutes and 1 second.

When we inspect example_12345, we see the fields and infer that the seconds are stored in the .Data field.

What other ways can you find help for a method? Read ?"?" and summarise the details.

Besides adding ? in front of a function call (i.e. ?method()), we may find:

- general documentation for a generic via

?genericName - general documentation for the methods of a generic via

methods?genericName - documentation for a specific method via

ClassName?methodName.

Extend the Person class with fields to match utils::person(). Think about what slots you will need, what class each slot should have, and what you’ll need to check in your validity method.

The Person class from Advanced R contains the slots name and age. The person class from the {utils} package contains the slots given (vector of given names), family, role, email and comment (see ?utils::person).

All slots from utils::person() besides role must be of type character and length 1. The entries in the role slot must match one of the following abbreviations “aut”, “com”, “cph”, “cre”, “ctb”, “ctr”, “dtc”, “fnd”, “rev”, “ths”, “trl”. Therefore, role might be of different length than the other slots and we’ll add a corresponding constraint within the validator.

# Definition of the Person class

setClass("Person",

slots = c(

age = "numeric",

given = "character",

family = "character",

role = "character",

email = "character",

comment = "character"

),

prototype = list(

age = NA_real_,

given = NA_character_,

family = NA_character_,

role = NA_character_,

email = NA_character_,

comment = NA_character_

)

)

# Helper to create instances of the Person class

Person <- function(given, family,

age = NA_real_,

role = NA_character_,

email = NA_character_,

comment = NA_character_) {

age <- as.double(age)

new("Person",

age = age,

given = given,

family = family,

role = role,

email = email,

comment = comment

)

}

# Validator to ensure that each slot is of length one

setValidity("Person", function(object) {

invalids <- c()

if (length(object@age) != 1 ||

length(object@given) != 1 ||

length(object@family) != 1 ||

length(object@email) != 1 ||

length(object@comment) != 1) {

invalids <- paste0("@name, @age, @given, @family, @email, ",

"@comment must be of length 1")

}

known_roles <- c(

NA_character_, "aut", "com", "cph", "cre", "ctb",

"ctr", "dtc", "fnd", "rev", "ths", "trl"

)

if (!all(object@role %in% known_roles)) {

paste(

"@role(s) must be one of",

paste(known_roles, collapse = ", ")

)

}

if (length(invalids)) return(invalids)

TRUE

})#> Class "Person" [in ".GlobalEnv"]

#>

#> Slots:

#>

#> Name: age given family role email comment

#> Class: numeric character character character character characterWhat happens if you define a new S4 class that doesn’t have any slots? (Hint: read about virtual classes in ?setClass.)

It depends on the other arguments. If we inherit from another class, we get the same slots. But something interesting happens if we don’t inherit from an existing class. We get a virtual class. A virtual class can’t be instantiated:

#> Error in new("Human"): trying to generate an object from a virtual class ("Human")But can be inherited from:

Imagine you were going to reimplement factors, dates, and data frames in S4. Sketch out the setClass() calls that you would use to define the classes. Think about appropriate slots and prototype.

For all these classes we need one slot for the data and one slot per attribute. Keep in mind, that inheritance matters for ordered factors and dates. For data frames, special checks like equal lengths of the underlying list’s elements should be done within a validator.

For simplicity we don’t introduce an explicit subclass for ordered factors. Instead, we introduce ordered as a slot.

#> An object of class "Factor"

#> Slot "data":

#> [1] 1 2

#>

#> Slot "levels":

#> [1] "a" "b" "c"

#>

#> Slot "ordered":

#> [1] FALSEThe Date2 class stores its dates as integers, similarly to base R which uses doubles. Dates don’t have any other attributes.

#> An object of class "Date2"

#> Slot "data":

#> [1] 1Our DataFrame class consists of a list and a slot for row.names. Most of the logic (e.g. checking that all elements of the list are a vector, and that they all have the same length) would need to be part of a validator.

#> An object of class "DataFrame"

#> Slot "data":

#> $a

#> [1] 1

#>

#> $b

#> [1] 2

#>

#>

#> Slot "row.names":

#> character(0)Add age() accessors for the Person class.

We implement the accessors via an age() generic, with a method for the Person class and a corresponding replacement function age<-:

In the definition of the generic, why is it necessary to repeat the name of the generic twice?

Within setGeneric() the name (1st argument) is needed as the name of the generic. Then, the name also explicitly incorporates method dispatch via standardGeneric() within the generic’s body (def parameter of setGeneric()). This behaviour is similar to UseMethod() in S3.

Why does the show() method defined in section 15.4.3 use is(object)[[1]]? (Hint: try printing the employee subclass.)

is(object) returns the class of the object. is(object) also contains the superclass, for subclasses like Employee. In order to always return the most specific class (the subclass), show() returns the first element of is(object).

What happens if you define a method with different argument names to the generic?

It depends. We first create the object hadley of class Person:

#> Person

#> Name: Hadley

#> Age:Now let’s see which arguments can be supplied to the show() generic.

Usually, we would use this argument when defining a new method.

#> Hadley creates hard exercisesWhen we supply another name as a first element of our method (e.g. x instead of object), this element will be matched to the correct object argument and we receive a warning. Our method will work, though:

#> Hadley creates hard exercisesIf we add more arguments to our method than our generic can handle, we will get an error.

#> Error in conformMethod(signature, mnames, fnames, f, fdef, definition): in method for 'show' with signature 'object="Person"': formal arguments (object = "Person") omitted in the method definition cannot be in the signatureIf we do this with arguments added to the correctly written object argument, we will receive an informative error message. It states that we could add other argument names for generics, which can take the ... argument.

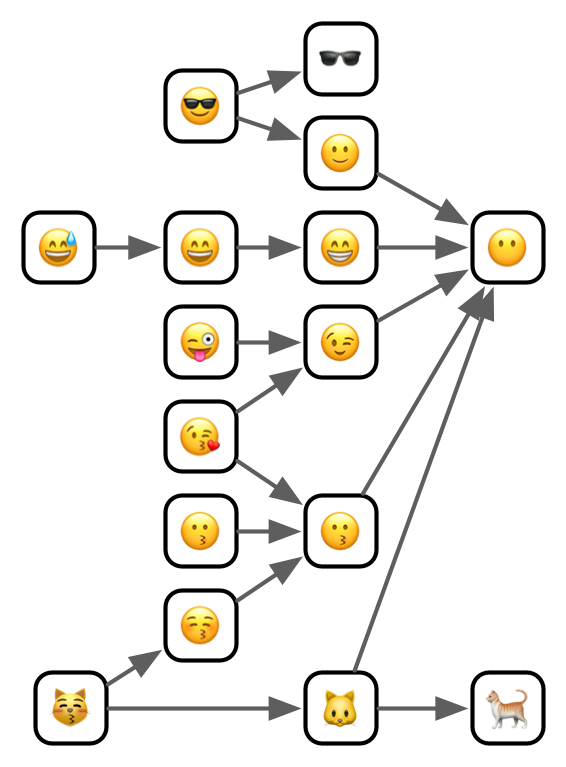

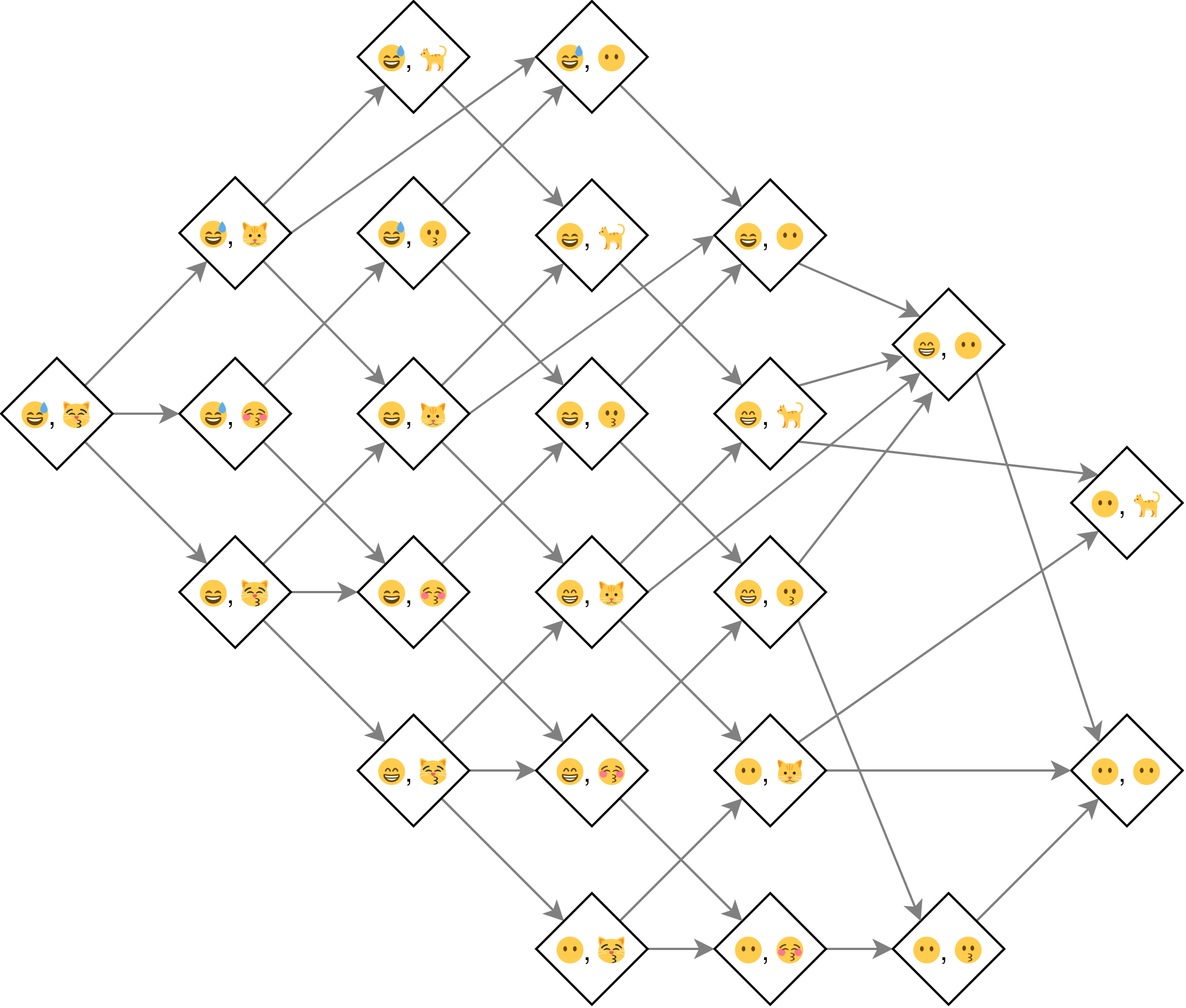

Draw the method graph for f(😅, 😽).

Look at the graph and repeat after me: “I will keep my class structure simple and use multiple inheritance sparingly”.

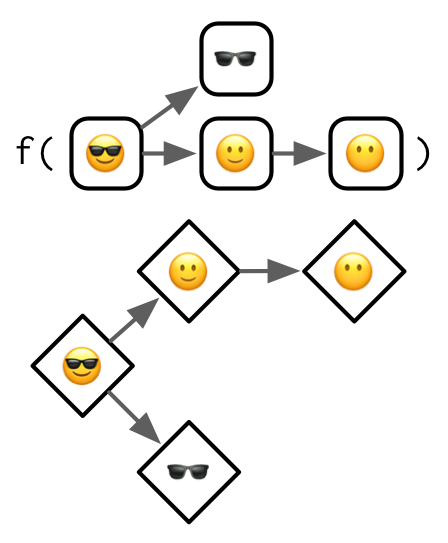

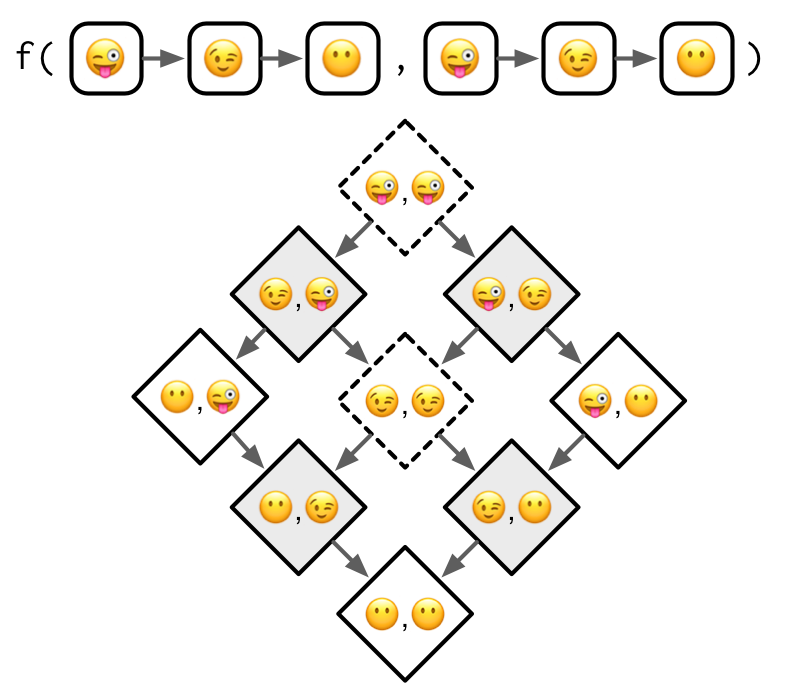

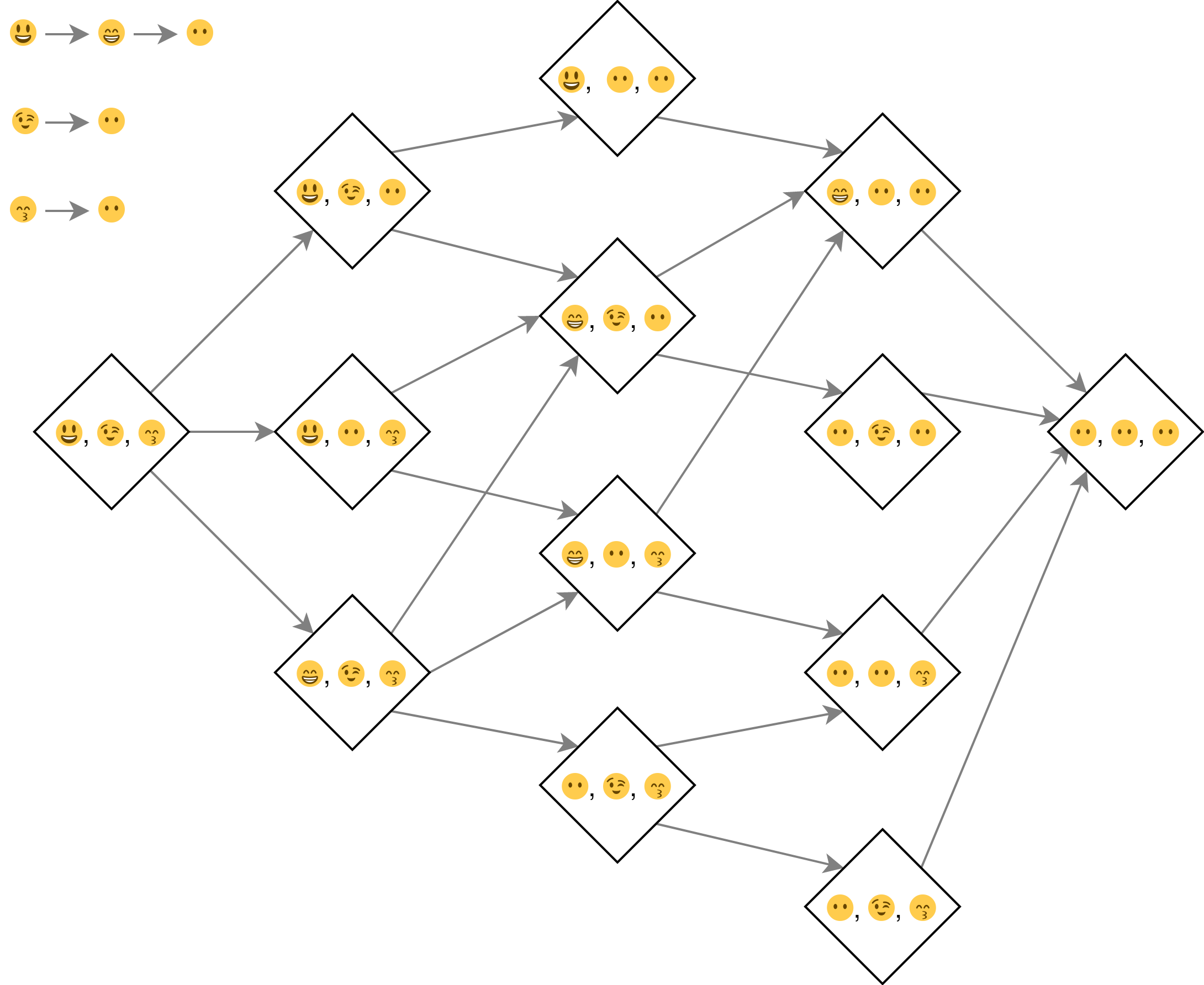

Draw the method graph for f(😃, 😉, 😙).

We see that the method graph below looks simpler than the one above. Relatively speaking, multiple dispatch seems to introduce less complexity than multiple inheritance. Use it with care, though!

Take the last example which shows multiple dispatch over two classes that use multiple inheritance. What happens if you define a method for all terminal classes? Why does method dispatch not save us much work here?

We will introduce ambiguity, since one class has distance 2 to all terminal nodes and the other four have distance 1 to two terminal nodes each. To resolve this ambiguity we have to define five more methods, one per class combination.

What would a full setOldClass() definition look like for an ordered factor (i.e. add slots and prototype to the definition above)?

The purpose of setOldClass() lies in registering an S3 class as a “formally defined class”, so that it can be used within the S4 object-oriented programming system. When using it, we may provide the argument S4Class, which will inherit the slots and their default values (prototype) to the registered class.

Let’s build an S4 OrderedFactor on top of the S3 factor in such a way.

setOldClass("factor") # use build-in definition for brevity

OrderedFactor <- setClass(

"OrderedFactor",

contains = "factor", # inherit from registered S3 class

slots = c(

levels = "character",

ordered = "logical" # add logical order slot

),

prototype = structure(

integer(),

levels = character(),

ordered = logical() # add default value

)

)We can now register the (S3) ordered-class, while providing an “S4 template”. We can also use the S4-class to create new object directly.

#> Formal class 'OrderedFactor' [package ".GlobalEnv"] with 4 slots

#> ..@ .Data : int [1:3] 1 2 2

#> ..@ levels : chr [1:3] "a" "b" "c"

#> ..@ ordered : logi TRUE

#> ..@ .S3Class: chr "factor"