Environments

Learning objectives

Create, modify, and inspect environments

Recognize special environments

Understand how environments power lexical scoping and namespaces

7.2 Environment Basics

Environments are similar to lists

Generally, an environment is similar to a named list, with four important exceptions:

Every name must be unique.

The names in an environment are not ordered.

An environment has a parent.

Environments are not copied when modified.

Create a new environment with {rlang}

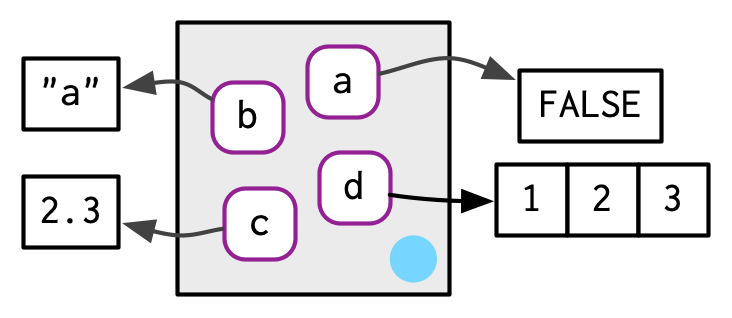

An environment associates, or binds a set of names to a set of values

Inspect environments with {rlang}

#> <environment: 0x00000242caa09348>

#> Parent: <environment: global>

#> Bindings:

#> • a: <lgl>

#> • b: <chr>

#> • c: <dbl>

#> • d: <int>By default, the current environment is your global environment

The current environment is where code is currently executing

The global environment is your current environment when working interactively

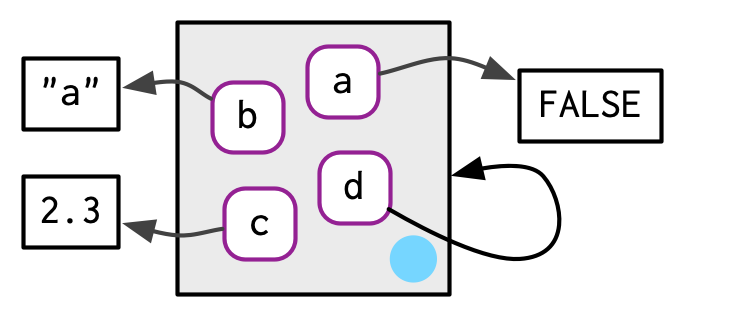

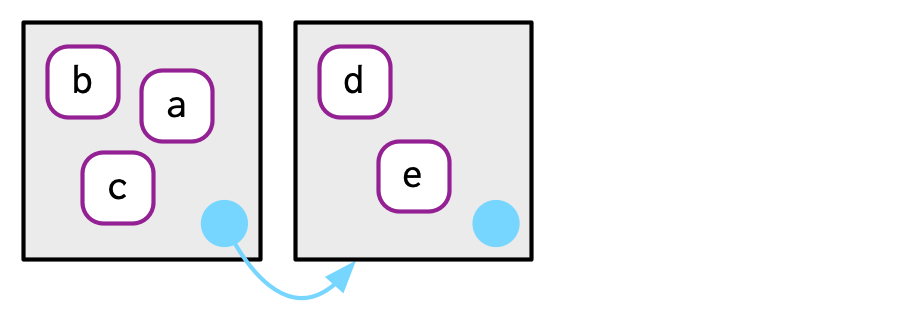

Every environment has a parent environment

- Allows for lexical scoping

#> <environment: 0x00000242cc7ab7e0>#> [[1]] <env: 0x00000242cc7ab7e0>

#> [[2]] $ <env: global>

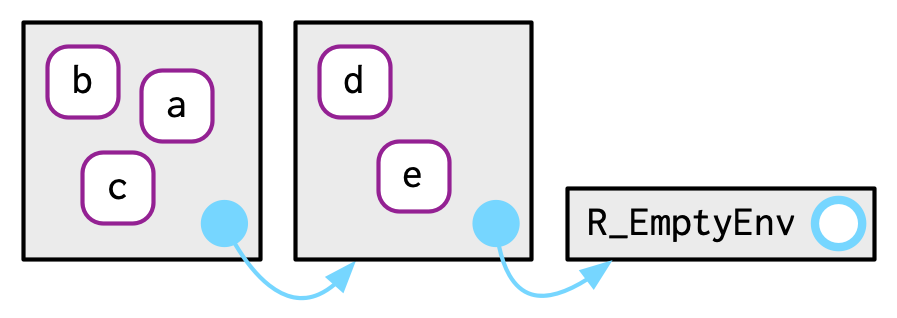

Only the empty environment does not have a parent

All environments eventually terminate with the empty environment

#> [[1]] <env: 0x00000242cc7ab7e0>

#> [[2]] $ <env: global>

#> [[3]] $ <env: package:stats>

#> [[4]] $ <env: package:graphics>

#> [[5]] $ <env: package:grDevices>

#> [[6]] $ <env: package:utils>

#> [[7]] $ <env: package:datasets>

#> [[8]] $ <env: package:methods>

#> [[9]] $ <env: Autoloads>

#> [[10]] $ <env: package:base>

#> [[11]] $ <env: empty>Be wary of using <<-

Regular assignment (

<-) always creates a variable in the current environmentSuper assignment (

<<-) does a few things:modifies the variable if it exists in a parent environment

creates the variable in the global environment if it does not exist

Retrieve environment variables with $, [[, or {rlang} functions

Add bindings to an environment with `$, [[, or {rlang} functions`

Special cases for binding environment variables

rlang::env_bind_lazy()creates delayed bindings- evaluated the first time they are accessed

rlang::env_bind_active()creates active bindings- re-computed every time they’re accessed

7.3 Recursing over environments

Explore environments recursively

7.4 Special Environments

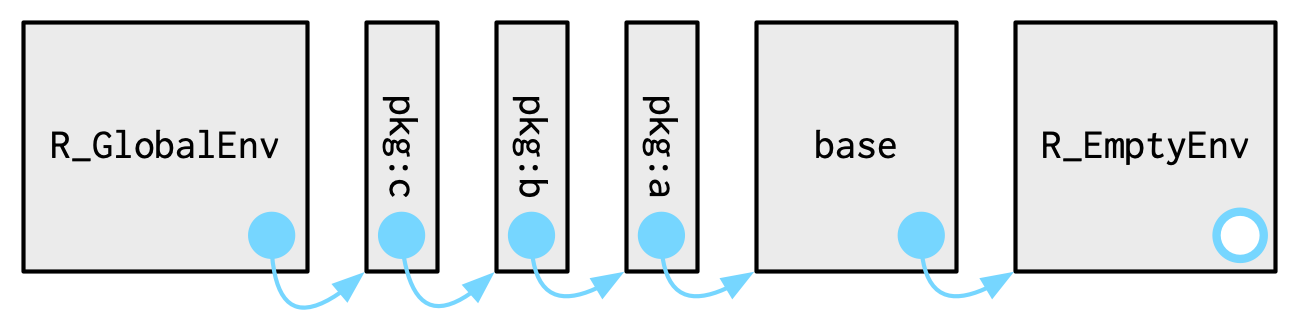

Attaching packages changes the search path

The search path is the order in which R will look through environments for objects

Attached packages become a parent of the global environment

The immediate parent of the global environment is that last package attached

Attaching packages changes the search path

#> [[1]] $ <env: global>

#> [[2]] $ <env: package:stats>

#> [[3]] $ <env: package:graphics>

#> [[4]] $ <env: package:grDevices>

#> [[5]] $ <env: package:utils>

#> [[6]] $ <env: package:datasets>

#> [[7]] $ <env: package:methods>

#> [[8]] $ <env: Autoloads>

#> [[9]] $ <env: package:base>#> [[1]] $ <env: global>

#> [[2]] $ <env: package:rlang>

#> [[3]] $ <env: package:stats>

#> [[4]] $ <env: package:graphics>

#> [[5]] $ <env: package:grDevices>

#> [[6]] $ <env: package:utils>

#> [[7]] $ <env: package:datasets>

#> [[8]] $ <env: package:methods>

#> [[9]] $ <env: Autoloads>

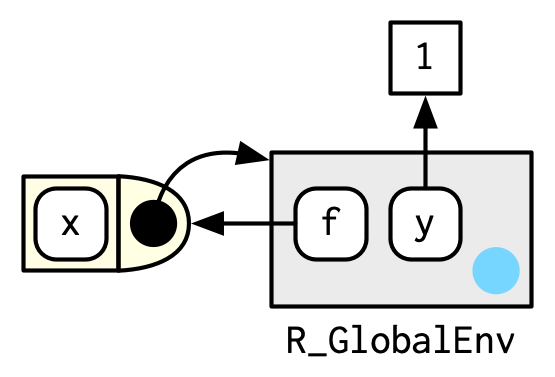

#> [[10]] $ <env: package:base>Functions enclose their current environment

- Functions enclose current environment when it is created

Functions enclose their current environment

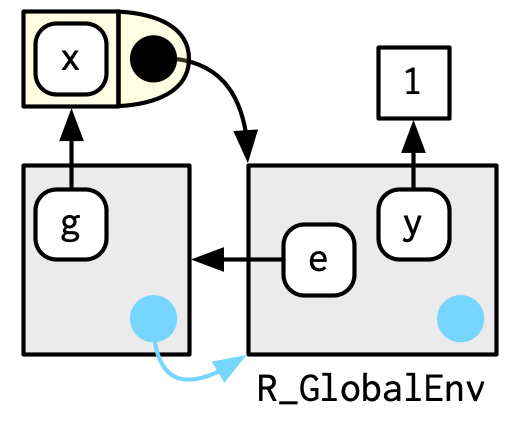

g()is being bound by the environmentebut binds the global environmentThe function environment is the global environment but the binding environment is

e

Functions enclose their current environment

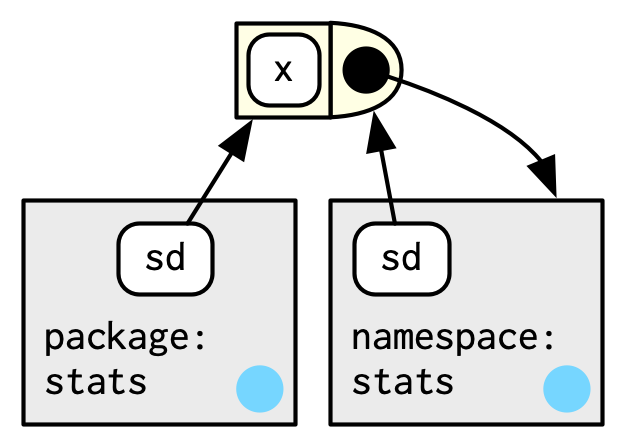

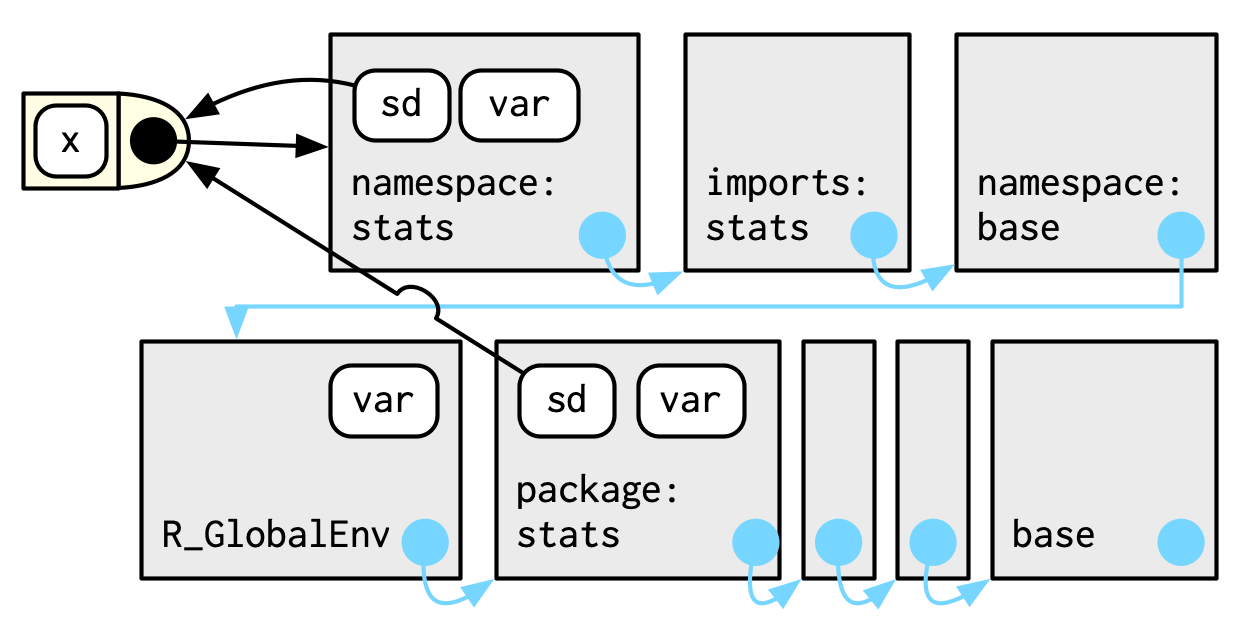

Namespaces ensure package environment independence

Every package has an underlying namespace

Every function is associated with a package environment and namespace environment

Package environments contain exported objects

Namespace environments contain exported and internal objects

Namespaces ensure package environment independence

Namespaces ensure package environment independence

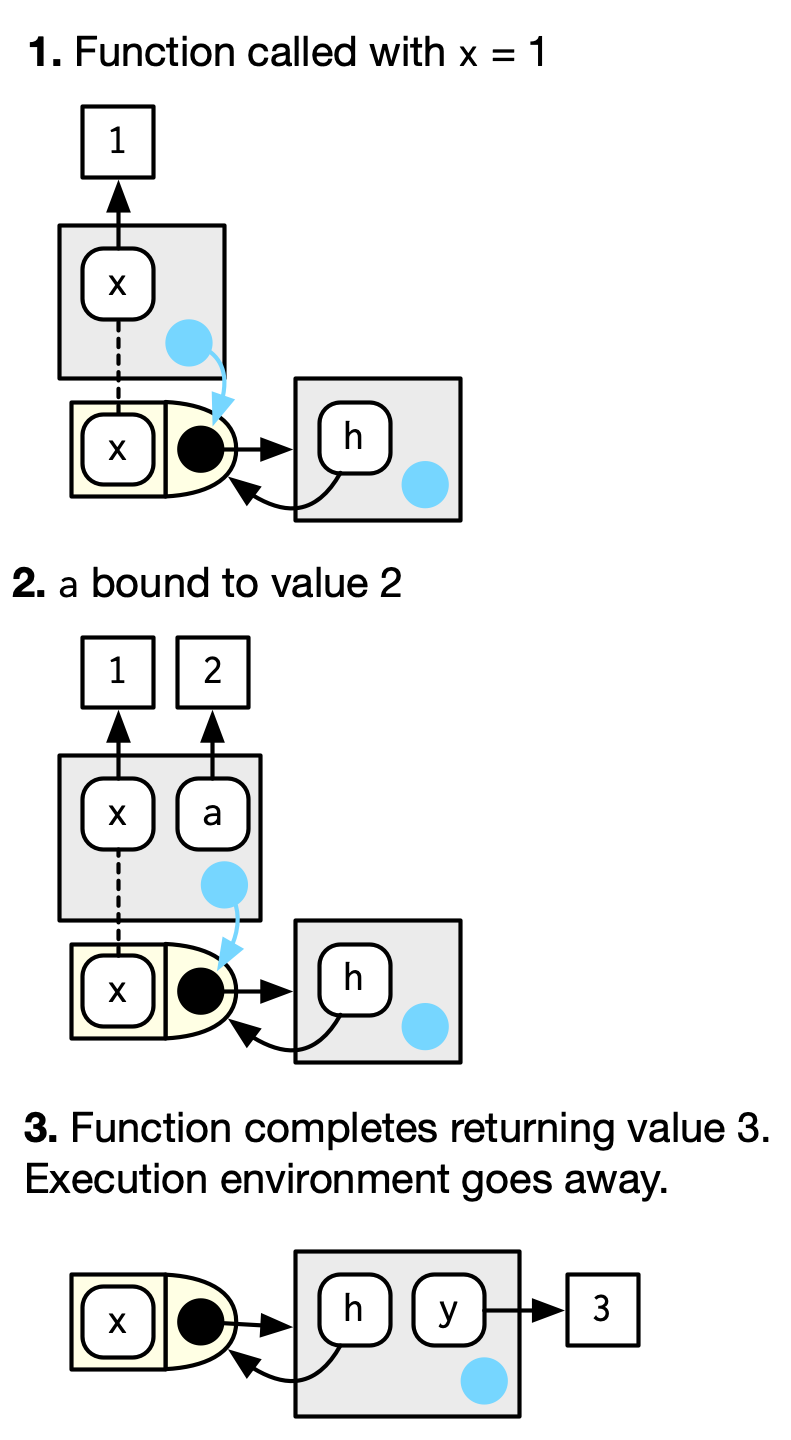

Functions use ephemeral execution environments

Functions create a new environment to use whenever executed

The execution environment is a child of the function environment

Execution environments are garbage collected on function exit

Functions use ephemeral execution environments

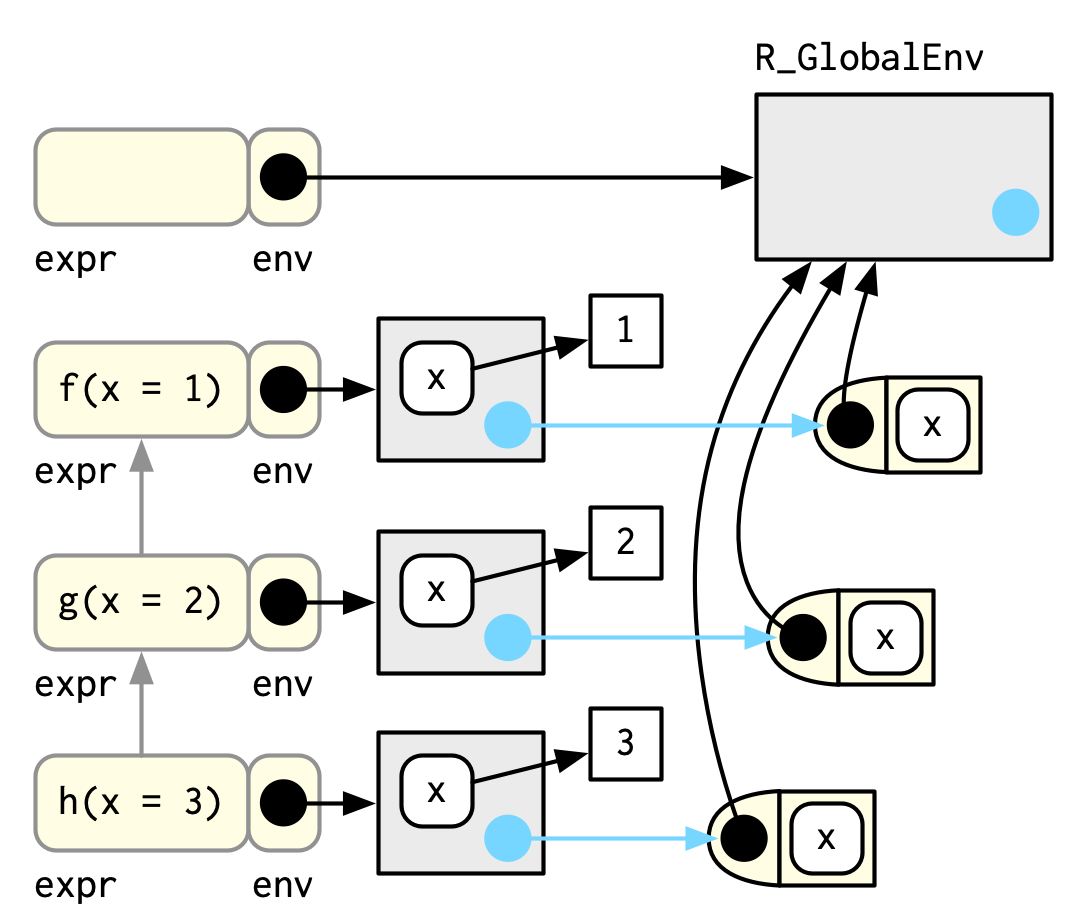

7.5 Call stacks

The caller environment informs the call stack

The caller environment is the environment from which the function was called

Accessed with

rlang::caller_env()The call stack is created within the caller environment

The caller environment informs the call stack

- Call stack is more complicated with lazy evaluation

The caller environment informs the call stack

R uses lexical scoping, not dynamic scoping

R uses lexical scoping: it looks up the values of names based on how a function is defined, not how it is called. “Lexical” here is not the English adjective that means relating to words or a vocabulary. It’s a technical CS term that tells us that the scoping rules use a parse-time, rather than a run-time structure. - Chapter 6 - functions

- Dynamic scoping means functions use variables as they are defined in the calling environment

7.6 Data structures

Environments are useful data structures

Usecase include:

Avoiding copies of large data

Managing state within a package

As a hashmap